It’s taken a few years, but I can now pinpoint the single biggest obstacle to getting shit done—and I am ready to reveal my secret.

In writing this, I think it is important to say that I consider myself generally to be an organized person. My bills get paid on time, client goals and projects are accomplished, and my consumption of a diverse range of media sources continues to enliven and enrich my life. I am a devoted user of Evernote, the single best note-taking and information-tracking tool I have found, and at the same time I also love my old-fashioned jotter, which fits in a pocket and doesn’t require any batteries (and can be “recharged” with Post-It notes, which are both thinner and cheaper than the index card inserts it comes with). While I am not formally a follower of David Allen and his “Getting Things Done” movement, I admire the concept and track some of the information sources in related spheres, such as Lifehacker.

However, my understanding of the impact of all these things on my life—together with two small children and a working spouse with her own set of needs and demands—has started to crystallize a little differently of late. In a pre-digital age, daily life could produce enough junk to overwhelm, just on its own. With email, the web, social media tools, and more options for tracking content and ideas and tasks than one can shake a stick at, “overwhelmed” can seen like an underwhelming description.

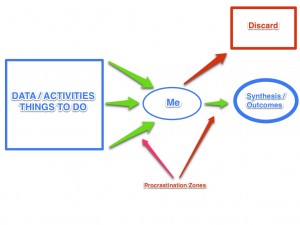

Fundamentally, though, I am not convinced that the volume of relevant information is that much greater than it ever was; the problem is determining relevance quickly—and then moving on. Thus, the single biggest challenge to efficiency? Procrastination.

For me, what I have noticed (in particular since my July 2009 about-face and decision to embrace Facebook and Twitter) is that there are two consistent—and generally well-meaning—procrastination zones that create problems, one as information is coming in, and the other as I’m pushing it out.

To address the problem in the first zone requires focus a heavier focus on relevance, and an effort to control (or curtail) digressions. This is the area where Facebook and Twitter can cause mayhem, along with all the things one needs to do for work (if not properly organized) or at home (like the non-tax-related papers one encounters on the way to doing one’s taxes).

To address the problem in the first zone requires focus a heavier focus on relevance, and an effort to control (or curtail) digressions. This is the area where Facebook and Twitter can cause mayhem, along with all the things one needs to do for work (if not properly organized) or at home (like the non-tax-related papers one encounters on the way to doing one’s taxes).

The second zone demands a high-intensity focus on information management, managing both the flow of materials and the (rapidly proliferating) new toys tools to help get things done. For instance, I have been contemplating switching my meetings to a psychiatrist-style 50-minute hour, (or a 25 minute half-hour) in order to guarantee time between activities, during which I can write down or assign tasks, file papers, respond to email, etc. It’s the delaying of these small tasks that often create larger and more complicated tasks hours or days later.

There is no doubt that sometimes procrastination and digression can be beneficial; it is during this time that the stimulation of creativity and free associations can help solve problems or come up with new ideas. But digressions in the digital age seem are much worse, it seems: it’s too easy never to turn things off, to keep going, link by link, from dawn to dusk and back again.

And that’s fine, as long as it isn’t stopping you from doing what you need to do.